Excerpt from The Adventurine by Marion Fasel on Substack. Click here for the full story.

Four years ago, when Beth Carver Wees told me she was working on a book with Sheila Barron Smithie about the American jeweler Marcus & Co., my first thought was, “That’s great.” I’ve never seen a bad or even a mediocre piece of jewelry by the New York firm that opened in 1892. Still, I wondered, even though the authors are academic heavyweights, if they would be able to find enough information to fill a publication. Very little was generally known about Marcus, the jewelry is comparatively rare and the company had been out of business since 1942.

Well, as it happens, Beth, who is the Curator Emerita of The American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Sheila, who has consulted on jewelry for The Met and is an adjunct faculty member at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art had already been researching for about six years when I learned about the project. All in, the collective effort involved in the production of the book, which was officially published on December 2, spanned approximately 10 years.

Marcus & Co. Three Generations of New York Jewelers is a landmark work, representing a substantial contribution to the scholarship of jewelry history. The 320-page publication is packed with 560 illustrations, including stunning jewels, many of which are paired with the original designs. Several images show the reverse of a piece so the construction can be seen. Great pictures of old New York and members of the Marcus family, as well as places where they lived, are among the other photographs.

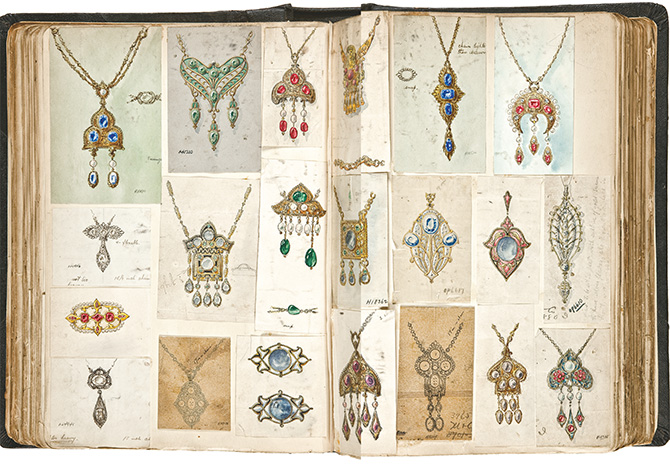

Selected pages of jewelry including several inspired by Islamic design from “Brooches and Pendants, No. 5.” Courtesy of Morse Museum

Marcus was not the only subject of study for Sheila and Beth. Throughout their book, they contextualize the Marcus story within the broader jewelry industry. They review how Marcus & Co. compared to others in New York City such as Tiffany & Co. and Cartier. Each chapter features an elegant map showing the sections of Manhattan where Marcus, their collaborators (such as the workshops they used), and retail competitors were located. The maps illustrate how the central shopping districts steadily marched uptown over the years.

The best part of the Marcus & Co. story, of course, is the jewelry. Before establishing his own firm, founder Herman Marcus partnered with the renowned Theodore B. Starr in 1864. Their shared passion for creative jewelry design is evident in an 1877 document in which they argued that jewelry is “a branch of the fine arts.” Creations by Starr & Marcus, including glorious cameo carvings depicting scenes from Greek mythology, reflect this attitude that continued throughout the history of Marcus & Co.

Side view of a black opal “Hindu” ring, ca. 1908–1910. Courtesy of Macklowe Gallery. Photo credit: Tony Virandi

Historical revival styles were a specialty of early Marcus & Co. work that reflected their substantive attitude about what jewelry should be. Long before Jacques Cartier’s famous trip to India during the Delhi Durbar in 1911, Herman, William, and George Marcus traveled there in 1895. It resulted in their Hindu-style. Some pieces were displayed at the 1897 and 1899 Arts and Crafts exhibitions in Boston where they were praised by the critics. One said, “The Hindoos and not ourselves are the ones who represent advanced civilization.”

Plique-à-jour enamel iris brooch, ca. 1905–1906, findings digitally removed to illustrate the fully sculptural quality. Courtesy of Macklowe Gallery. Photo credit: Bret Wills

Some of the most amazing Marcus & Co. jewels are the Art Nouveau plique-à-jour enamel floral designs. These pieces are far more three-dimensional than even some of the greatest work produced by French masters including René Lalique and Georges Fouquet. Produced a few years later than the peak Art Nouveau period overseas, the Marcus flowers differ from the slightly sinister tone of most European work. The American botanicals are realistic as opposed to fantastical and as vibrant as spring.

Marcus & Co., ruby, yellow and white diamond orchid brooch, manufactured by Oscar Heyman, 1936. Courtesy of Sotheby’s

The prevailing notion that American jewelry crafted during the 1920s and 1930s does not measure up to European standards is dispelled by Marcus & Co. One reason is the firm used Verger, the same French manufacturer Cartier employed for their clocks and objects. They also enlisted the exceptional talents of Oscar Heyman, a New York manufacturer who rivaled its overseas counterparts in the jewelry industry.

Another thing Marcus did in the 1920s to cement its creative status was employ the celebrated multi-hyphenate creative Rockwell Kent to illustrate its advertisements. After three years of a fruitful relationship, the artist’s temperament, desire for a raise and thoughts about how his work should and should not be used are the types of juicy behind-the-scenes details covered in Marcus & Co.: Three Generations of New York Jewelers that make the book a must-have for any serious jewelry library.

Marion Fasel writes about history and contemporary trends in The Adventurine newsletter on Substack. She is the author of 11 books focusing on 20th-century jewelry design. In 2021, Marion curated the exhibition Beautiful Creatures: Jewelry Inspired by the Animal Kingdom at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.